The Pioneering Women of the Zigzag Hotshots

This multimedia project was made possible with support from The Smokey Generation, the American Wildfire Experience and Mystery Ranch. Header image taken by Beth Gorill.

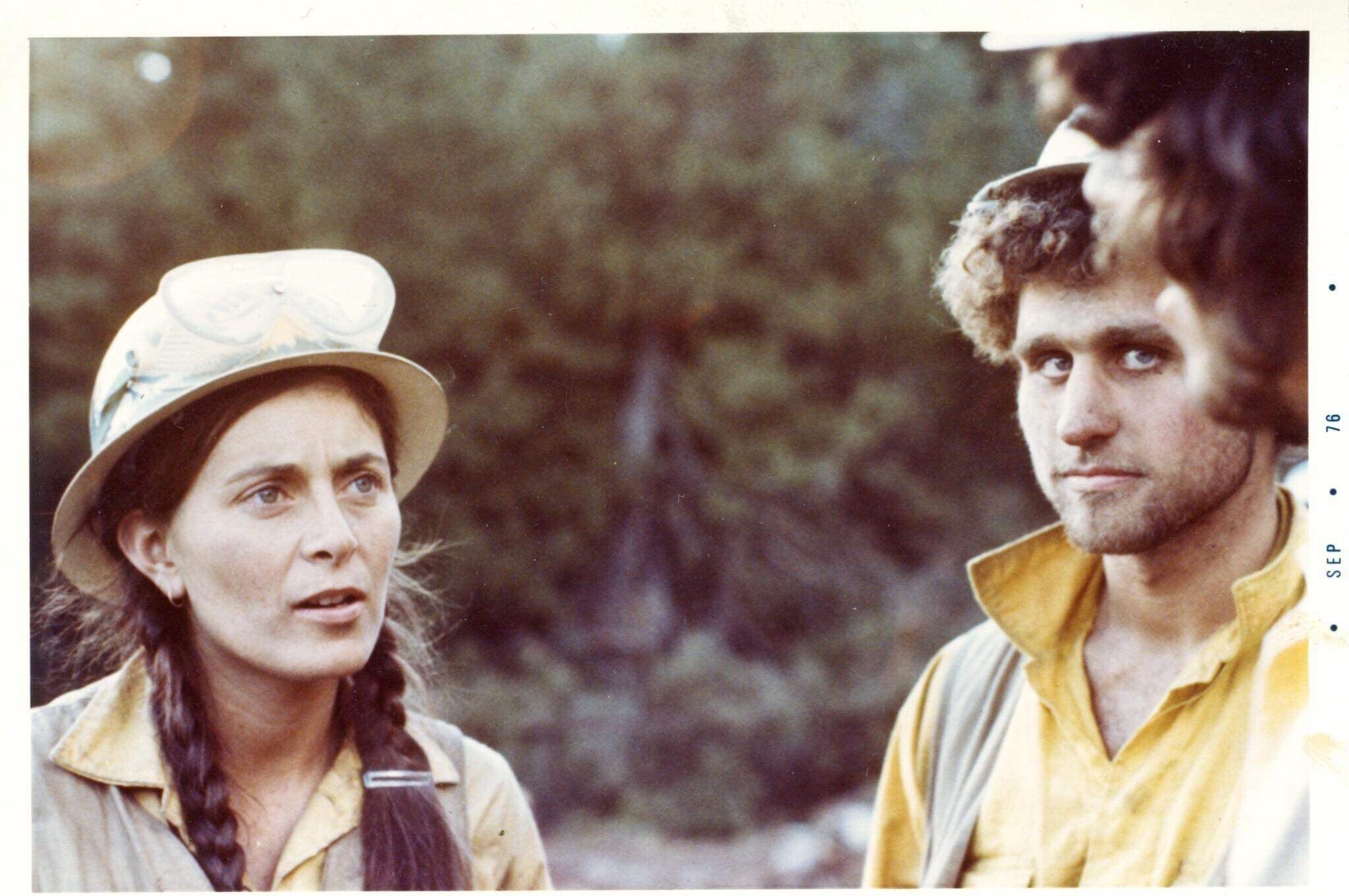

The walls of the Zigzag Hotshot building are lined with crew photos, one from almost every year since the early 1970s. The photos show people weighed down with gear, their ash-covered cheeks and chins contrasted only by radiant smiles.

Some of them hold saws, most of them tools. They’re wearing yellow Nomex or their red crew shirts — red has been the Zigzag Hotshot crew color since the 70s. Gender is nearly indistinguishable amongst the faces, save for a few women with dreaded ponytails or a messy braid.

I’m a current Zigzag Hotshot. I’ve only been on the crew for two years now, but it occurred to me recently that I don’t feel much different from those women on the wall — I can see myself in their faces, in the smiles that can only result from days and days of hard work. I recognize those smirking grins, those exhausted eyes, those messy ponytails, the filthy hands, faces, arms.

In this I find some sort of solace, a rare generational link between myself and the women who paved the way for me, a connection formed in challenging shifts, in hikes that have made me consider every single decision I’ve ever made, in nights on the ground and the sense of humility that can only really come from seeing fire act as if you weren’t there. In these women I see a happiness unmatched; in them I see confidence and humility, the beauty of a woman doing precisely what she wants to be doing, and doing it well.

I set out to learn more about the women before me, about the seemingly insurmountable pushback they faced, the harassment and sexism and anger that met them as they became some of the first women to pursue careers as hotshots. But it wasn’t just hardship that they talked about—far from it. They told me about how hotshotting had changed them, or in some cases how their life experiences before and after hotshotting were far more formative—that fighting fire was just another stepping stone in a life well-lived. They talked about the relationships they formed, about the fires they worked, about the shifts they’ll never forget, and the funny moments that tend to fill the cracks of summers spent working hard with the same 20 people.

What I found in speaking to these women is that wildland firefighting has changed tremendously since they were swinging tools in the 70s, 80s and 90s. And whether or not hotshotting changed those women, there’s absolutely zero doubt that those women changed hotshotting—for the Forest Service as a whole, for Zigzag, and for women like me.

The First Woman of Zigzag IHC

Kimberly Brandel worked for Zigzag from 1976–1980—five seasons in a time when it was unheard of to hire a woman, let alone retain her for more than a season or two. She was, as far as we know, the first woman to work on a hotshot crew in the Pacific Northwest (Washington and Oregon, also known as “Region 6” in Forest Service terminology), and was the first woman ever hired to Zigzag—though some women had “filled in” for an assignment or two in earlier seasons.

I spoke to Kimberly over the phone early this fall, just a day after my second season with Zigzag had ended. I’d received my belt buckle the day before—this is a rite of passage in the fire world. Most hotshot crews hand out belt buckles following a crewmember’s second or third season, and at least on our crew, there’s a number on the back of it: mine was 182, which means only about that many Zigzag Hotshot belt buckles exist, riding the belt loops of those who’ve come before me.

Kimberly is refreshingly honest about her first years of hotshotting, and doesn’t sugarcoat her experience in a world that was still very much averse to having women around. There was occasional harassment, frequent yelling. She was told she didn’t belong there. Other crews made snide comments. In her first seasons, it was made very clear that no one wanted her there.

“When I look back on it, I’m proudest for having survived, having done it, and for putting up with a lot of harassment from men. It was so hard sometimes being the only female. I just wanted to prove that I could do it.”

And she could do it. She went on to become a squad boss on Zigzag before moving up in the fire world, receiving a master’s degree in fire ecology, and ultimately going on to fill roles as a division supervisor and safety officer before retiring from fire in 2010.

“I just did it as well as I could do it and didn’t piss and moan,” she said. “That’s all you really can do.”

Kimberly’s honesty is matched only by that of another Zigzag alum, Eileen Grace. Eileen is fiery, so much so that she proudly earned the nickname “Hellbitch” during her seven seasons on the crew from 1981–1987—eight seasons if you count the 1980 season when she filled in for Kimberly, who left early to attend Colorado State University. Eileen will tell you herself that she had a reputation for being a “bitch,” a distinction that sometimes has more positive connotations for women in the fire world than negative.

“I didn’t have the persona of niceness that is so popular these days,” she said over the phone from her home in Pendleton, OR. “I was more vicious than anyone else on the crew in terms of maintaining and setting the standards of the crew…and I demanded that the women perform equally or superior to the men.”

This wasn’t just her being a bitch, though. This was her looking out for the well-being of the crew, making sure that everyone who was there deserved to be there and making damn sure that everyone working under her, especially the women, understood the importance of doing good work, safely.

“We had seven women on the crew [in 1982], so you can imagine the attention that drew,” she said. It should be noted that no other hotshot crews were hiring that many women that early.

“I was leading that pack, so if I f*cked up, anything with tits would be set back half a century.”

This is less an over-exaggeration and more a telling description of how women were—and, sometimes, still are—viewed in the fire world: as a liability.

But Eileen remains fierce in her assertion that while women do bring a unique dynamic to the fireline, they should be hired just like the guys—on merit, not gender. So it goes without saying that nearly every woman who walked through Zigzag’s doors in the 80s was more than worthy of her position on the crew, and had earned it the old fashioned way—by working really, really hard for it.

Gina Papke

One of the women who came through Zigzag’s doors in the 1980s was Gina Papke.

I met a man recently who’s worked for the Forest Service for over 20 years. While talking, it didn’t take us long to realize a commonality in our backgrounds—we’d both worked for Zigzag, albeit with a couple decades separating our times there. He’d worked there in the late 90s, during the tenure of Gina.

He mentioned her name and summarized her influence on him simply:

“She made me tough.”

After 12 seasons of working in fire, Gina became one of the country’s first female hotshot superintendents in 1991—the year I was born. She was second only to Margaret Doherty, who was the superintendent on Lolo Hotshots for the 1989 season. Superintendent is the lead position on a crew, often requiring no less than 10 years of work in other leadership positions on a shot crew to be considered.

Gina made a lot of people tough in the 10 years she worked as superintendent, and because of her single-handed and concerted effort to diversify her hiring, a whole lot of those people were women. She made an effort to get five women on the crew every season, and on years with a slew of quality applicants, she’d get up to eight. Even now, this ratio is unheard of; I’ve never worked on a crew with more than four women, and have never even heard of one with more than five. As Kimberly Brandel said about her time as a hotshot, a crew is a pie made up of 20 pieces, and for a long time, only one of those pieces was set aside for a woman. It’s been 40 years since Kimberly was a hotshot, and yet this analogy still rings true on a majority of modern crews.

“We always ran with five or six women,” Papke says of her time as superintendent. Recently, Zigzag has generally run with two to four women, including my squadboss Sandra Sperry, who has worked on hotshot crews all over the Northwest for the better part of a decade. Making sure there are at least a few women in the ranks seems to be a continuation of the inclusivity perpetuated by legendary Zigzag superintendent Paul Gleason, who was the crew’s superintendent from the late 70s until Gina took over. He was just as intent on diversifying as Gina was when she took over, and that ideology continues to this day.

“Women sought me because I was the only female hotshot superintendent, and we were known to be a good crew,” she says. “For me, it was just giving them an opportunity to see what they could do with themselves. Women underestimate themselves, but I saw something in them that they were going to do well; they were going to be in shock because it’s very physical, but I knew they’d do well.”

So why women? This is a question I often ask myself: why would any crew want me? I can’t lift as much as most of the guys, and before I got into fire in 2016, I’d hardly touched a power tool, let alone a chainsaw. But it’s people like Gina—people with a refined ability to see potential, to find people’s individual strengths and capitalize on them—who know that women bring an unparalleled backdrop of experience and a distinct mindset, which can all contribute to a more effective (and safe) group dynamic. Though, from a purely physical standpoint, Gina also found that women had a few key qualities that made them not just good firefighters, but exceptional hotshots.

“They tended to tame the crew down, and brought a different intellect to the line,” she says. “But women also have more endurance, pound for pound—the women could dig line all night long, and when it came to hiking or working all night long, they could just go forever.”

Recognizing each individual’s strengths is one element of being a hotshot superintendent that Gina spoke to the most, and it’s particularly important to consider when women are brought into the mix. The balance of physicality, safety and effective decision-making is almost like assembling an “orchestra,” according to another female Zigzag alum that I spoke to, Juli Bradley (1986–87): You have the brute force, you have the decision makers, you have those with endurance, those with speed, those with strength, and together you create a dynamic, cohesive unit with a blend of unique backgrounds, experiences and qualifications.

“You have to appreciate what each person can bring, and between sexes I think that often gets overlooked,” Gina says.

Paul Gleason was particularly strong in this element of leadership, and in that way undoubtedly influenced the way the Zigzag program was run nearly from the onset. He recognized the need for diversity on the line, not just by hiring more women but by hiring minorities, and by maintaining a standard of ground-up respect that is, to this day, drilled into Zigzag rookies the very first day they show up to work.

“Better decisions are made when you have a cross section not only of women but minorities—the whole gamut,” Kimberly Brandel said. “I was really lucky that I worked for Paul Gleason because he really sought input from everybody.”

Gina didn’t borrow too much from Paul Gleason’s leadership style, though. She knew the importance of developing her own style and, ultimately, her own legacy.

“I had to be me when I became superintendent,” she said. “When I got the job I said ‘I can’t fill his shoes, I have to fill my own shoes,’” she said.

Gina’s path to the superintendent position started in Clallam Bay, WA, the logging and fishing town she grew up in on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula; it’s a small outpost on the extreme northwest corner of the peninsula where she grew up cutting shake locks and planting trees as a teenager. When she was fresh out of high school in 1979, she hitched a ride with a man on the peninsula who convinced her to find work in the woods.

“I was hitchhiking one day and this guy picked me up and asked me what I was doing, and I told him I was going to apply for the Youth Conservation Corps,” she said. “He said ‘Don’t do that, apply for the Forest Service instead,’ and he walked me through the process of applying. He said he’d take me to Olympia and help me fill out an app. I put in for it and got it.”

She found work on a brush disposal crew, which had quite a few other women on it—an influx (in the Northwest, anyways) that she theorized must have resulted from the women’s liberation movement of the late 60s and early 70s.

“We were just coming off of the women’s rights movement,” she said. “That brought more women out like, ‘hey, I can do this and I’m just going to take over and make it happen.’ And a lot of those women stayed for a long time.”

“But at that time California hadn’t had any women at all, maybe one or two but they wouldn’t last, [the crews] were purposely washing them out,” she added. “Washing out” is the term used to describe forcing an applicant to quit. Usually, it involves a lot of hard physical training, and particularly up until about the early 2000s, also included a fair bit of hazing and harassment.

There is a bit of a disparity, to this day even, in the prevalence of women on hotshot crews in California versus in other states, but in the 1980s it was even more unlikely to see a woman on a crew there. So when Gina joined Northern California’s Lassen Hotshots in 1985, she was forced to battle a culture that was wholly averse to having women around.

“When I got on Lassen, it wasn’t as if they’d never had a woman before but their whole attitude was that if you wanted to be on the crew you either needed to date someone or there needed to be two of you—or you’re not going to make it,” she said. “I was like ‘are you kidding me?’ They made my life hell, but I stuck it out.”

She then moved back to Zigzag—where she’d worked from 1983–1984 as a crewmember—the next season, to work under Gleason once again.

“Gleason, he had this look that we all knew—it meant that we had to dig in,” she said. “The longest shift I ever worked was for Gleason, 52 hours. It was a long shift digging line. They don’t do that anymore.”

There’s quite a bit more about Gina’s hotshotting experience that no modern hotshot will likely ever experience. For one? The lack of radio communications—which is probably an under-appreciated advantage in today’s fire operations.

“We used to go more commando—they didn’t have as many radios as they do nowadays, so we just had to go on instincts,” she said. “I remember going to lightning strikes all the time; they’d split us all up and we’d go out and be working lightning strikes without a radio. It’s like, you might not see the rest of the crew for a week or so and then your fire would be out and you’d start walking out, like ‘I guess we should go find someone.’”

“There was a lot more yelling back then,” she added, laughing.

Stories like these abound when speaking with Gina—30 years of some of the more extreme fire experience you can get lends itself well to great storytelling. Gina told another story of a fire where she and some of her Winema Hotshot (where she was a squad boss in 1987) crewmembers were without food for three days while smoked in (meaning helicopters were grounded and unable to deliver food or supplies) on a fire near Chetco Bar, OR.

“We were in there for three days. At the end of a fire season, when you don’t eat for three days, you already have no reserves left—it was everything in our power to just move,” she said. “Not having food for that long took a real toll.”

After some experience with Winema, Gina went on to be a “leader” on Zigzag, which would likely fall under the “captain” title on modern crews. She took over as superintendent when Gleason moved on after the 1990 season.

I had met up with Gina and Juli at a cafe in Zigzag, OR to interview them for this story, and Gina brought along stacks of photo albums—filled to the brim with images from her time on Zigzag. One image, in particular, shows her in 1988 in her Nomex, gear and chainsaws scattered around her, with a huge smile on her face. Her stance is casual and her upper body is strong—she said herself that pushups and pullups were always her strong point.

“You look really happy,” I said—an admittedly obvious observation.

“I really was,” she responded while looking at the photo. She ran her finger over the image in its plastic sleeve, pausing, before turning the page.

Gina Papke as a leader on Zigzag in the late 1980s.

While at the cafe, I asked both Gina and Juli what they took away from hotshotting—what it taught them, or how it changed them. Juli was quick to answer:

”I think it taught me that I could, whatever it was, I could,” she said, her voice breaking slightly.

I tend to relate to this element of the “female hotshot” experience the most—if there’s anything working for Zigzag has taught me, it’s that I can do it, regardless of what ‘it’ is. Unlike many of the women who worked for Zigzag early on, I don’t recall knowing that about myself before discovering the challenges of working on a hotshot crew, and I’m not ashamed of that. Hotshotting has changed me deeply: I have worked harder than I ever thought possible, formed relationships with incredible people I would have never met otherwise and developed skills that women in their 20s don’t traditionally have the opportunity to develop. I’ve somehow developed a love for hiking chainsaws uphill, for eating bad food in beautiful places, for the way sleep feels after a hard day, and for the way fire feels when you’re digging line next to it. Fire has set me on a course I could have never imagined five years ago—all this, because of the work done by the women before me.

As we finished our chicken noodle soup and lukewarm coffees at the Zigzag Cafe, I posed the same question to Gina—”how has hotshotting changed you.” She had a much different answer than Juli and I.

“There were things you had to fight for, you just knew what you had to do to keep up and make a difference,” she started. “As Deanne Shulman, the first female smokejumper, used to say, ‘Did the Forest Service change me or did I change the Forest Service?’”